Barton Smith, professor of mechanical engineering at Utah State University, talked with us about pitch aerodynamics, seam shifted wake (SSW) pitches and how they work, cutters, sinkers, the discoball changeup, laminar express, and all sorts of interesting pitch design concepts. Follow him on twitter: https://twitter.com/notrealcertain or on the web at https://baseballaero.com. This episode contains LOTS of visuals. Watch the video version on YouTube here.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS

EP47 Transcript – Seam Shifted Wake, Discoball changeups and Everything Baseball Aerodynamics with Barton Smith

Watch the episode below:

Dan Blewett: All right. Welcome back. This is episode 47 or the morning brushback I’m your cohost, Dan Blewett I’m here remotely. We’ve got an awesome guest today and of course I’ll enters my cohost first Robert Stevens. Future mayor of Chicago is here.

Bobby Stevens: I’m good. These last two guests are making me question my school background.

Yes, it’s going to get even rougher today. I think. And then our yesterday Barton Smith, a professor from Utah State University, Barton, how are you?

Barton Smith: I’m good. Thanks for having me. So

Dan Blewett: if you’re new to our show, we had a fun Twitter thread after Alan Nathan’s episode, which was our previous episode. Um, Barton and I were chatting a bunch.

I’ve read some of his work in the past about, uh, he works in aerodynamics and has a Canon where he’s shooting baseballs out all day and testing, spin, and it’s pretty fascinating stuff. So we were talking about the cutter and. Got done a pretty long rabbit hole and decided let’s talk about this on the show.

And I think one of the, the things that unites us is we don’t really know what’s going on with cutters. They’re fascinating enigmas. So, um, Barton, how did you get into baseball, aerodynamics?

Barton Smith: Uh, it’s funny cause it’s come full circle just this morning that my kid pitches, he was about nine or 10 and somebody was talking to him about two seam fastballs.

And I asked the question, which you would think everybody knows the answer to. What’s the difference between the two seam enforcing. And, um, I’ve been chasing that stupid question ever since. Uh, we fired, um, uh, two-seam in a forest, the amount of a pitching machine and I would encourage her, but yeah, do this.

If you have a pitching machine, that’s. That’s consistent and you’ll see that they do exactly the same thing. There’s no distinction between them at all, which that got me started. And, uh, I’ve, uh, I’ve gone back and forth about this many, many times since then, but it’s just, like you said, simple questions that you think everybody knows the answer to that you can really find a very deep.

Dan Blewett: Um, so let me talk about that, because that kind of broke my brain right off the bat. You’re saying two seamers don’t do anything different compared to a forest senior, is that correct?

Barton Smith: Not if you put them in a pitching machine, because I probably should have made this distinction. Pitching machines are a hundred percent efficient.

Yeah. If it’s, there’s only two machines I know of in the world, one is traject a brand new machine coming out of Toronto, which I think everybody’s going to hear about soon. And then I’ll give a shout out to those guys. It’s an amazing machine that can put gyre on the ball. And the Washington state has one that can do that too.

And I’ve got to borrow it or use it once, but that’s a very rare commodity. Anything wheels that you normally see and the candidate we have is a hundred percent efficient. So it seems that the seam effects that cause two seamers to be different. I think happened when you impart a little bit of gyro to the ball.

Dan Blewett: Yeah. So when you throw a less than a perfect spinning fastball, so if you drilled a hole and spun a four seamer and you drill the same hole through a two seamer and you threw them both, they’re gonna go, they’re gonna do the same thing. Yes. That’s really interesting. So basically what we could say then is that two seamers are essentially capitalizing on human error in a good way.

Is that a reason? Yes,

Barton Smith: that is a good way to put it, but if you took that same error and you put it on a forced him, it wouldn’t have the same effect.

Dan Blewett: Yeah.

Barton Smith: Yeah. Go ahead. Are we

Dan Blewett: talking about like, if you hold it as a four-seam grip, you’ll hold it as a, like a traditional two-seam grip and then throw it. In a vacuum they’ll neither want to we’ll do anything other than just stay straight,

Barton Smith: not in a vacuum.

That the important point is that. And I have, here’s my two seam ball that is perfectly efficient if I throw it so that this rod. Stays perpendicular to me as it goes in and out in a way for me to seem in a forest, seems the same thing. If it’s got some gyro, then all bets are off and a lot of things can

Dan Blewett: happen.

Okay. So there are, so the pitches themselves are different pitches. Like. When pitchers are throwing them. I’m just trying to wrap my head around because I’ve seen some balls that are unhittable

Barton Smith: pitch your sand. And I still do that. What’s happening is they do, they have put some gyral on it and, and, uh, and then it’s doing something different.

So, and I think this is all about to become really apparent because of Hawkeye data that it’s gonna, um, that’s going to bust it open. We just, uh, I was just telling them earlier that, uh, Tom tango put some data out on Twitter this morning, or last night, late last night. That shows this for my friend, Gerard Hughes.

And, um, and so I think now that we can no, how to look at it, it’s going to be really obvious. Um, and that’s just starting. Okay. The important point is that there was a caveat I put in there. If you load the balls into a pitching machine and they’re going to be the same and that what that does is lock it into a hundred percent efficiency, no gyro.

And then the same.

Dan Blewett: Gotcha. So let me back you up a little bit, because you’ve already mentioned at least one word that I’m sure some percentage of my audience doesn’t really know what that means, which is gyro. Can you give us a brief overview? Imagine that I’m a 12 year old and Bobby’s an eight year old, because I think that would represent our, our split here.

I’m so early for that, Dan. Um, can you explain the key, the key components of what makes baseballs move or not move.

Barton Smith: Sure. Um, and I’m gonna use this, this baseball to do it. So, um, for now let’s not worry about the orientation. This is two seam, but that’s, that’s not worried about that. So the ball spins, if, if this ball is coming towards, you unite through it, then that’s a, that’s a fastball it’s spinning backward.

It’s gonna, and that’s going to generate force that way because it was what we call Magnus today. Um, if I. Find a way to throw the ball like that, which is what a lot of change ups do. It’s going to move that way. Uh, I hope I have that direction, right? Yes. It’s going to move that way if it’s coming toward you, but I’ve met this effect.

So that’s what we call tilt. Or spin axis. And, um, this is a fast ball. That’s a change up. Um, then when you want to talk about gyro, which you need to talk about, if you want to get into things like sliders, what that means is this rod is no longer both into the rod or not at the same distance from you when it’s closer, that’s gyro, that’s basically it.

And so it happens if I’m throwing the ball and I don’t have my hand directly behind the ball. Uh, and I, I should acknowledge you. I’m not a pitcher. I don’t throw very well. And so I’m kind of faking it when I say things like this, but I’ve seen it. So this, uh, this would be a a hundred percent efficient pitch on.

And let me back up efficiency is a metric of gyro. A hundred percent efficiency means there’s no gyro and we call it efficiency. Because that means that all of the spin is contributing to Magnus

Dan Blewett: effect Putin wasting.

Barton Smith: Yeah. Yeah. When you have some gyro, not all of it is. Yeah. And so, um, you have less movement due to the Magnus effect when you have some gyro.

But, uh, gyro introduces other interesting possibilities. So, um, and I’m not going to attempt to say what a slider would look like. Cause I really struggle with that. Um, yeah, no, I’m just, I’m just not going to do that.

Dan Blewett: Well, I think they’re also really hard to, and we were talking about this off camera as well, which it’s really hard to visualize what pitches look like at this slow, like you’re showing the orientation.

It’s like, Oh, this is what the pitch did. It’s like, okay, great. But like Bobby is a hitter. He knows what a slider looks like at full speed. Probably couldn’t tell

Barton Smith: I have the opposite problem. I can’t tell what they look like. It takes speed. So, because I only looked at them in high speed video.

Dan Blewett: Yeah. Well, and that’s, I think that’s part, well was part of our cutter discussion.

Is that okay? There’s so few people that actually throw cutters that there’s so few people that can say I’ve hit off them consistently and like really good ones, or I’ve caught them consistently. I’m obviously more catchers than probably hitters. Who’ve called good cutters. But, um, I mean, Bob, a good slider has that dot.

Where does the dot typically reside on a slider? Um,

Barton Smith: on a good slide.

Dan Blewett: I actually, I feel like a good slider. Doesn’t have that dot. Like it’s almost like you don’t see it. Um, It’s almost right in the middle. If I can, man, it’s been a while since I’ve seen a slider, like in the box, but it’s almost like right in the middle,

Barton Smith: but if you think this point spinning around is I’m going to throw it, something like that.

And so I see as it’s coming to work me, I see the ball spinning, something like that.

Dan Blewett: Yeah. I mean, from the dot itself is red. It’s the same. Like you see the sea, you see like a, basically it’s circling around the seam. So if that yeah. Posts to that ball that you have barn is if you put that pole or that pipe through it and it, and an intersect the witness seems.

Yeah. Yeah. So you’ll see, like the seam that’s closer. Um, and you would,

Barton Smith: you would have that coming right out there, but it’s not

Dan Blewett: as, I mean, I never say look for the dot on a slider. I’ll never tell a player that, because I don’t also recall seeing it. Like every time I saw a slider, like, I’d see more of the hand.

And you kind of see the Bach, I mean, really good sliders. You don’t eat. It’s almost, they look like fastballs. I mean, it’ll either

Barton Smith: right, but that’s, what’s making yeah.

Dan Blewett: That’s, what’s making like

Barton Smith: this

Dan Blewett: pitch tunnel that like, when teams are now developing like pitch, uh, what do they call those damn pitch tunneling?

Areas, I don’t know. Pit pitch tunnels is just good way to describe the way different pitches will like separate from each other. If you throw a fastball that goes straight through the zone, you throw a slider of that same trajectory, the way it would track the

Barton Smith: Cubs,

Dan Blewett: the Cubs have this like area of the.

The stadium where they go and work on their pitches. And it’s like just high Def cameras. I don’t know what they call that area, but

Barton Smith: Oh, the pitching lab? Nothing.

Dan Blewett: Yeah, maybe they might call it the pitching lab. It’s tough. It’s so the backs of the dot, I would say not, you don’t see the dot on very good sliders, but.

You’d see it right in the middle and it’s definitely red, like the seams. So one of the things we want to get into is, uh, Barton, you’ve done a lot of work with seam shifted wake, and you’re going to kind of share that with us today, but I also want to hear, so what is essentially the mix? So you’re just talking about a slider.

Like when I would teach kids, I’d say, Hey, the slider is kind of a combination of, you have to kind of get to the front of the ball. So in part, a little bit of like forward spin, kind of, and then you also get through the side of the ball to impart this bullet spin or the gyros spin. So it’s like a mixture of the two curve balls are not that way.

So could you kind of break down what you would say? Like the cocktail is for, you know, whatever smattering of pitches you’d

Barton Smith: like. I’m sure from what I know and, and I’m, I’m just, you know, the year ago I knew nothing. So, uh, I know about a year’s worth of intense study on this, and I’m trying to teach my son how to throw these and that’s, that’s, that’s what I know.

So, um, as I said, uh, there’s a few that are really easy. That’s a fast ball and, uh, That’s a curve ball. So, um, and that’s, if you throw the ball from a very high arm slot, if you’re more, uh, three-quarter like a lot of people are then that fast ball spins like this, I’m sorry, this or ball spins like that. So generally your curve ball, if it’s working well, has the opposite movement.

Of your fastball. So I, something I said on Twitter a while ago, and it seemed to really cause a little bit of a stir or was that a fast ball and a curve ball or? Yeah. And that’s how I see them because they have opposite break and eight spin ups away. They’re thrown totally differently. Like you were saying, curve ball.

I throw by. Well, I guess they don’t break my wrist. Right? That’s something that coaches teach the kids sort of like that. And they spend a lot, one of the things that’s interesting me about curve balls is watching them. They spend more than a fastball does, which is to me kind of surprising biomechanically.

You can spin the ball faster with your fingers on the front of them than you can from behind. And as a side effect of that, they move slowly because you’re not pushing them with your strong fingers. So they tend to be really slow. And I think that’s part of their. Appeal is that they’re very different speed than fastball.

Um, so then change ups. Um, I understand about as well as I do cutters, uh, your video was very interesting to me, man. I don’t know if you have a baseball there, but, uh, maybe show that, uh, show that grip that you were, that was in your YouTube video, but at the end of the day, Um, a lot of modern change-ups spin, uh, Michael Augustine calls a disco ball for reasons that I’m hoping are becoming obvious as they do that.

But usually they’re, they’re a little tilted. And, uh, what that does is that makes all the Magnus effect sideways and, uh, and so they move, uh, arm side generally. But they don’t have much left. So they, they drop. And I’m going to talk about seam shifted, wakes in just a minute. And I think a lot of pitchers, Strausberg Scherzer, and a lot of others are using seem effects to make that drop even more.

Uh, so, um, that’s changed slider. We were just talking about a cutter is a fast ball that is thrown, I believe. And this is what Dan and I were talking about

Dan Blewett: or is it Bobby’s thing or is it, yeah,

Barton Smith: so basically with your hand up the longer behind the ball, so that there is some general component to your fast ball and that’s consistent to me with the small difference in speed that they get.

The small difference in speed comes from the fact that your hand, your fingers aren’t pushing as efficiently as they are if you’re like that. So they’re usually a couple miles an hour slower. Similarly, on the two seamer, going back to my, the tumors are basically less efficient for seniors. I think that’s why they’re usually a little slower.

Um, quite often, if you look at someone’s sink or a two seamers, just a couple miles an hour slower than their 40 sr. I used to think that was cause of drag. But now I think it’s because of the way it’s thrown. It’s a little, you’re getting a little less push with your fingers. And I think that that’s about as much as I know, I am a fan of you.

Darvish said I should probably be able to mention that others, but I don’t know them well enough.

Dan Blewett: Yeah, for, um, I’m just curious as like, as someone who doesn’t pitch, like you hear pitchers talk and I don’t have a baseball, but they’re holding a baseball. They’re talking about putting pressure on one finger, putting pressure on another finger.

You know, if you’re putting, if you got pressure on the same, like, this is what I do, and this is what makes it, makes the ball do this. Like how much of that do you think you teach or have you taught as far as pressure on fingers? And then did you use as a pitcher? Because that’s all I hear when you’re sitting next to pitchers.

Well, I, so I don’t know that you can actually like put pressure on the ball. Like I’m squeezing it hard with my index finger, but not with my middle finger, because pitching is such a fast fluid, like relaxed motion. Like your arms are very wippy obviously, I don’t know that people are actually pushing on the ball at the moment of release.

Like they say they could, that doesn’t seem like that’s a reasonably possible. Um, all those things, like people thought that they were like really whipping through the ball, like their hand was laying back. And that’s why they were getting whipped. We’ve debunked that through high speed video too, like the risk is pretty much constant as you accelerate the ball.

So it, uh, you know, if your wrist is pretty much constant, I don’t think that there’s really going to be a difference in finger pressure either. How could there be, I mean, your arms going super deep, you know, 6,007,000 degrees per second. So I think when guys say I put pressure on it, I think that means that’s how they start it in their glove.

Like, so they might be like, I’m pushing a little bit hard here, like, as it comes, go time. I think they’re just that they’re just overloading. The ball is I think or what they actually, me, I don’t have any real proof of that, but I don’t see how that’s reasonable now. I mean, like with my curve ball grip, like I can stick it in there where there’s some pressure naturally, like, because my fingers are forced.

So there’s kind of like an elastic. Holding it they’re like, you know, my fingers are tense because it’s jammed there, but I wouldn’t call that pressure in the sense that you kind of think of putting pressure on something. I would just say that. Like pressure is formed because of the grip. But I’d say it’s really just the grip.

I wouldn’t say it something different and separate, but I don’t know. You hear like random guys will throw like one seamers and it’s kind of like highlight, literally getting the ball on one same. I mean, maybe it’s just cause there, but that’s just like, it’s, it’s holding a sinker like this where it’s just coming off that one scene.

But I don’t know that you’re really, again, I think that’s something like there’s a lot of athletes that say they do stuff. I’m sure Barton you’ve heard tons of. Stories about that. Like guys think they’re doing one thing and then you get them on camera, you slow it down and they’re not actually doing that.

I think that’s what finger pressure

Barton Smith: you feel in your head and what actually happens.

Dan Blewett: And

Barton Smith: I think recognizing that as a big part of being successful at this stuff,

Dan Blewett: because if you know someone saying, Hey, I, yeah, I put, I put more pressure on the inside of the ball. It’s like, well, How do you know that you do that when you release it?

When it actually matters? There’s like you can be putting pressure in your glove. You can be putting pressure all the way through here, but if you’re not putting pressure, when it comes off your fingertips, does it matter? I don’t think that like, how could it, so I think that ends up just kind of being like the way you set the ball in your hand.

I

Barton Smith: had a major league front office guy who I won’t name. He told me that never listened to pitchers about what they’re doing.

Dan Blewett: Well, I had a teammate and I was like, dude, you’re very dumb. He, what he was saying was he threw a spike curve, a knuckle curve, and he was telling me that he used his knuckle. To push the ball forward.

I’m like, first of all, let’s look at the orientation of your fingers. First year friend. Like you’re going to push it this way. That’s not the way the wall spins the wall and this way you’re shoving it towards I’m. Like that literally makes no sense. So we got on iPhone, but this was 2014. Like an iPhone five and it wasn’t quite conclusive.

It was to me, but to him, he’s like, Oh no, it’s like, it literally makes no sense what you’re wearing. I’m very, I’m very curious to who that was or you, what you want to known him.

Barton Smith: There there’s a cute, you know, you give somebody a Q and a makes them do what they want to do, and that’s good enough, right?

Dan Blewett: That is, that is, that is true. So back to change ups, and then I want to get the same shift or awake, but, um, so one of my things, and this was just happenstance when I started teaching change-ups back in 2010. So I taught myself one in college in 2005. I just like tinkered asked around a little bit. And then I came to this group where I have two fingers on the top thumb on the bottom fingers, doing nothing on the sides.

And it helps me get on the inside of it. And I threw that all through college. It became a pretty good pitch. I threw it in pro ball. It became a very good pitch and had a lot of heavy movement. And what I said, teaching full time in the off season, doing lessons, I realized. And I don’t know if every lesson instructor does it this way, but you’re like, I want to be able to give a consistent experience and teach the same things from one kid to the next and be reproducible.

Just like, you know, you go to Chick-fil-A, you get the same food every time. So I’m like, you can’t, there’s a million, you talk to kids, especially five years ago. It’s like, Oh, I throw this grip or this grip or this grip or this grip. I’m like, what does the change of do? They’re like, well, it goes straight or it goes slow.

Does it move sometimes? Like, it’s just a crapshoot. Whereas if you talk about a slider, a curve ball, There’s a dis there’s a defined, spin to a curve ball, right? Like a curve ball. That’s good. It has topspin. Like, there’s no question about it. You can throw it like, hold it different ways. But a curve ball is a pitch that has topspin a, slider’s a pitch that has a mix of gyro and topspin.

And with a change up, it was just like the wild West. It’s like, I could just pick any eight different grips and I don’t really know why it goes slow. I just hope that it does. So I’m like, that’s stupid. So I’m like, I’m going to try to find a defined spin for my change ups so that when I teach this, it’s like, I can just reproduce it.

And so I did, and basically I started trying to explain how my change, it moved the way it moved. And I said, well, okay. I think you get about 5% of the speed reduction from your grip. Cause these fingers are just weak or you hold it deep in your hand and then you get 5% by losing speed into spinning it on the inside.

Like you prone it over the top of it a little bit early. And so you get that 5% and 5% and that’s where you get your consistent. You know, change up speed reduction and your sink on your run. And that proved to be true over time. And kids will throw it. I mean, I have 10, 11, 12 year olds that’ll throw this change.

I don’t usually teach to blow 12, but they can consistently get on the inside of the ball and create that like angled, tilted, spin axis. And I think this is essentially the same thing that disco ball, um, But then it was funny because over the years you started seeing a couple of big leaguers throw it that way because of, from me, but just like they figured this out King, Felix was one of the first ones is Jane.

It was filthy and then Strasberg. And there’s a lot of guys adding it now, but I think they’re figuring it out. They’re like the change of should have I have a defined characteristic set, not just like, I pick a random grip and like, they throw this starfish ones. Like if you throw a pitch like this, it’s going make, maybe you do something different every time.

It doesn’t, that’s not a reliable way. If you’re, you know, As a pro pitcher, your pitches are your tools. It’s like, you know, you want your tool to do this, to be sharp and ready to do the same thing every time. So, anyway, I don’t wanna get too far sidetracked on changeups cause Barton, you’ve got a bunch of slides and some stuff to share because you have a lot of really interesting, um, aerodynamic stuff.

So do you want to jump into seam shifted wake? Can kind of explain to us what that is and where you feel like it’s going

Barton Smith: explain

Dan Blewett: it very slowly. Okay.

Barton Smith: Let me just count about the change up though, because you know, as a, as a baseball bat, You know, when a changeup is introduced to a kid, you’re trying to throw the ball slow, but move your arm fast then as you get, you know, and I’m not sure this is a recent evolution in baseball, but all of a sudden now change up is about a very specific movement profile.

And, uh, and I think, uh, that’s a pretty interesting evolution and. This year in the majors, I think what’s happening either. We’ve had had an influence, which I doubt, or there’s a lot more high speed video. So we’re seeing a lot of these disco balls, all of a sudden. And they’re pretty interesting. So I’m going to try, I have a, our presentation on seam shifted wake it’s online.

If anybody’s listening and wants to see it, I can send them a link. Uh, but, uh, I’m, won’t give you the full hour. The idea is, um, you know, I think a lot of people for over the years have had an idea that seems matter. I think a lot of people think that seems to make the magnet bigger and they don’t. Um, they do have an effect on drag.

Bigger seems to give you more drag. And I think that had a lot to do with the home run search Ellen, and I could go around about that all day. I think he has a bit of a more nuanced view than I do. Um, but, um, but in terms of making the baseball move and break, um, until recently, I don’t think, uh, there was much acknowledgement that seems matter.

Um, Bauer Trevor Bauer has started suggesting probably about five years ago that the orientation of the ball matter relative to its axis. That’s a how, and just to. Describe what I mean, here’s two different orientations relative to the access. The access is the rod, but if you look here that rod is coming out of a different point, relative to that logo, that’s a different orientation relative to the axis.

So he was the first person that I know of that suggested that that matters. He was trying to achieve a pitch where you would see. A part of the ball, like this part down here, that’s smooth, a large part of the time. I think what he was achieving was a seam effect. And he didn’t know that at the time. I think, I think he’s got around my point of view on that, but, um, um, so, uh, what it seems do.

Um, well, I’m going to, I’m going to share my screen here and I’m gonna, I’m gonna try to keep this dial back a little bit and not go totally bananas. I’m asking a professor to exercise restraint when speaking

Dan Blewett: well, jump in and I’ll try if, is there something that I don’t understand then that’s a good gateway for.

That other people probably don’t as well. Cause I’m still on the layman’s side with a lot of your super technical stuff. So this will be good. So if you hear me jump in, I’ll just ask you probably asked you to clarify some stuff.

Barton Smith: Sure. I appreciate it. So I’m going to start with a golf ball and I like golf balls because they are much easier to understand than baseballs because they’re the same everywhere.

They have the simple pattern it’s uniform and that golf ball is moving to the left. At about 90 miles an hour. Um, we’ve done a measurement here that I won’t get into, but it allows us to see the wake of the ball. And it’s important to note here that the wig, and don’t worry about whether it’s red or blue.

That’s just showing us where the wake is. And hopefully you guys can appreciate that. That’s what that is false. Move in that way. I put arrows here where the wake starts see that, that you got this red stuff and it leaves the ball right there forms the wake same thing up here. And they’re both these two arrows that are about the same point on the ball.

If I spin the ball, those two arrows move, this one moves back. This ball is spinning like that. This one moves back here that one moves forward and the wake is now tilted down. That’s Magnus effect. That’s what, that’s. What makes your golf ball ride if you hit well, it makes it slice. If you don’t hit it.

Well, that’s why a good forcing pass ball has bride to, it tends to stay higher than it should because Magnus effect. This is what I don’t want to talk about. This is, this is the counterexample to, uh, w I want to talk about, because, um, that’s been understood for a very long time, but what we’ve learned more recently, Is that if you have a seam, that’s in a certain range of positions, it can cause that wake to form early on, on that side.

So this is an example of this and then the magic location or near a slice through the ball. That’s perpendicular to the direction it’s moving. So this ball is moving straight to the left, but it looks like a wake is tilted upward. Which means being pushed down and that ball’s not spinning at all. So, uh, this isn’t Magnus effect, and this is the whole idea of seam shifted wakes.

Is causing a seem to reside in kind of the same location as the ball spins around so that you keep this weight tilted like that and push the ball in some direction. Um, I didn’t have enough background here to explain this, but in general, when you have a ball, that’s moving through the air, you get high pressure on the front of it, which I think is kind of intuitive.

You get low pressure on the sides. And since the wake is all at the same pressure. And so since this low pressure up here got cut off because the, because the wake formed early, that means I have more low pressure on the bottom of the ball at the top. That means being pushed down. I don’t think about it for

Dan Blewett: me.

And so this wall, this wall wouldn’t be spinning or this would happen. And so if it spins and if I’m, you’re going to cover this later, just stop me and tell me we’re going to get there. But if this ball’s spinning, then does that wake form just the same or this has to, it has to maintain its orientation throughout flight.

Barton Smith: There’s a couple of different possibilities. So let’s talk about the one that I want to spend most of my time on say that the say that that ball is spinning and it’s spinning kind of, kind of like this. So that there’s an access that’s through a vertically then, um, and that I can make that seem still inspire that spin.

Be here most of the time.

Dan Blewett: Yeah.

Barton Smith: The seam effect is in kind of 90 degrees from the Magnus effect. So

Dan Blewett: that’s why the disco ball change up, applies there where it’s going to be

Barton Smith: pushed out. Imagine this is a change up in the access is straight up and down and spinning, spinning like this. And actually here is my, I have a disco ball change up ball here.

Here it is. So if I spend that, I’m going to try to get that in front of the camera. You can see that that seam up there on the top is just usually hanging out in that same spot.

Dan Blewett: Yeah. Okay.

Barton Smith: That makes sense. And if I throw that say, it’s, it’s moving that way. It’s moving that way. Sorry. And I tilt it with some gyro.

So that that seeing now is near the top of the ball. As it’s moving this way. That’s what this go ball change at this and this scene. Causes that wake to form early on the top of the ball and push the ball downward. So, and I think that the disc ball change up is the easiest seam shifted wake pitch to, to understand, um, note that if this was a change of like we’re talking about the magnet sports would be pushing straight into the, into the page, but the seam effect is going to push it down.

Dan Blewett: Okay. So let me ask you then if I’m a, like a Chris sale, of course, Chris, sale’s not exactly siren, but say I’m a sidearm pitcher and I’m throwing it to steamer. Are we going to get the same exact effect?

Barton Smith: Yeah. Well, that’s a, that’s a, you’re a good straight man. Cause that’s Jerry Hughes. Um, and I want to talk about him a little bit, cause he’s, I think his arm slots quite a bit like Chris sails, if I’m not mistaken.

Um, let me just a cop in here that I met Jared,

Dan Blewett: his photos are,

Barton Smith: he takes a picture like this. So somebody had a post on Twitter another year, another awesome picture of Jared Hughes. And that was before I met him. And, uh, didn’t know about these awesome spring training pictures, but he is right arm guy.

That’s his sinker. So this is not a change. It’s a sinker, but he throws it at such a low arm slot. It has about the same amount access is a change up. And he is able to cause that ball to have a seam effect that pushes it downward. And you can see that seam spinning around the top of the ball. It’s a spinning something like this.

And it sinks like crazy. And what’s interesting about these pitches. I think you made the comment to me that sometimes somebody says, Hey, nice curve ball. When you throw a change up. The reason they’re saying that in my opinion is because the ball is being forced down or it’s not fall a traditionally, we think of a change up as falling, but this pitch and a good disco ball change are falling.

They’re being pushed down by the scene. And that w and a curve ball is pushed down by Magnus spec. So I think we have that, you know, we can see that with our eyes, that balls, that falling it’s being, it’s being pushed. So if you have a low enough arm slot, yeah. You can throw a sinker. And I think a lot of sinkers type, um, it has the same effect that pushes it down.

But

Dan Blewett: so even then, sorry, go ahead, Bobby. I’m going to say norm, go ahead. Actually go because my question’s probably going to be like, well, is this via video loops through? You can still see him get a little bit to the top, which is probably going to put like, there’s a little bit of, eh, right as he hits it.

Whereas if you’re just a side or a side arm or just throwing, I’m going to get off camera. I’m gonna move a little bit. If you’re directly to the side of it. And there’s cause you can see like a little bit of wobble and obviously like those been visualization right there shows that it’ll wobble, but yeah.

You know, when you’re a lower Armstark guy, if you throw a nice clean, like good spin access to steamer, it’s going to have that same thing. But without that wall, well, is that going to be a difference? Cause I don’t feel like when you throw, you just have to roll ball sidearm, it doesn’t just sink like crazy.

Like I can throw like a shortstop throws the ball across the diamond and it is pretty true. So I guess my question is how does that differ? Like what is he doing differently that gets all this sync, whereas a shortstop throws it sidearm. And it doesn’t get that much thing.

Barton Smith: Right? There’s two things notice that this pitch has a lot of Chiron component to it.

So 21 degrees, or if you prefer, I think it says 93% efficiency. So that’s crucial. The other thing is that it’s oriented. It’s funny. It’s like you said, it’s not straight to seeing it’s, uh, the, the ball is oriented differently in his hand. Now talking to Jared. This was nothing that he ever tried to do on purpose.

Oh, he did realize, yeah, it works better when I do that. So I’m going to do that. It’s only recently that he’s come to understand that that’s crucial, but let me show you the VR to me, this is even more exciting. This is his four seamer and the four seamer. It’s a seam effect on the bottom of the ball from the seams and it rides.

So this is being pushed upward. So what I what’s so exciting to me about Jared Hughes. As he throws these two pitches with exactly the same speed RPM and axis. And they are, they’re forced in two opposite directions by the seams. And that is, like I said, Tom tango kind of shut a light on that last night on Twitter.

His grip

Dan Blewett: is the same

Barton Smith: on both of these. Now the grip is different, the grip stuff. Right. But

Dan Blewett: when you say the grips different. So the four-seam I assume he’s holding with his index and middle finger. It looks like, I don’t remember. Can you, you go back to the change

Barton Smith: of a, it wasn’t a change up. It’s a sinker sinker.

Yeah, here’s the sinker.

Dan Blewett: Okay. All right. So the sinker and the forest team are both being thrown index finger, middle finger dominant. Different grip.

Barton Smith: Yeah. Different, uh, different right. Different grip. I, uh, I need to get through my head that the way you put the ball in your hand as a grip.

Dan Blewett: Yeah, yeah.

Barton Smith: Orientation. But yeah, that’s really all it is. And, um, and so one of the fun things about working with Jared is that you can put as much gyro on as you want. I say to them, Hey, can you do 80? He does 80. And, um, and so we’ve been able to mess around with that a bit, find that there are the, basically the more gyro you get, the more as a gyro angle approach is 45 degrees.

There’s a lot more room to make seams do stuff for you. So, um, I just recently discovered also that Joe Smith. Throws a four seamer and that gets ride from SIEM. So he’s even lower. He’s actually a little bit submarine, I think, but his four seamer rises as a result of seams.

Dan Blewett: Okay. So when you say ride, just to be clear ride to you means it.

Gotcha. Perfect.

Barton Smith: Even though there’s none for Magnus, really? Yeah. In the case of Joe Smith, if anything, he has downward Magnus force. Jerry is getting a little bit of upward Magnus Wars. But it’s overcome by the same force

Dan Blewett: out there who don’t know Joe Smith. He’s a little bit mercy, a good amount below sidearm.

Now I think he’s changed a little bit throughout his career, but he’s been like a 14, 15 year journeyman reliever. I can’t. I know he’s with the Astros last I saw him, but he was maybe a little bit below sidearm. I can’t

Barton Smith: remember. Tom is a little bit below sidearm. He opted out this year, so we haven’t, unfortunately we have to get him out Hawkeye to see what that’s doing.

Uh, as a side note, I love to tell the story. My dad, excuse me. My dad’s name is Joe Smith. Joe Smith was with the Cubs briefly. I’m a Cubs fan. So my dad made me a Joe Smith, Cubs Jersey. I got to tell Joe Smith about that awhile ago, he tell you, he thinks I have the only Joe Smith Jersey out there.

Dan Blewett: Nice.

Nice. That’s interesting. So Dan, isn’t that pretty common as far as like we’re talking about orientation essentially. Like that’s what a lot of pitchers will. If a guy with a bad slider wants to learn from a guy with a good slide or the first thing they talk about is how he holds it and then what he thinks about like how he throws it.

But I would think the first thing you guys talk about is, is the grip. No. Well, and so that’s the interesting thing. And I’m curious your thoughts at this, pardon is that. With the other, like there’s with the curve ball, there’s essentially one way to throw it, like, put it here, your finger on the inside of the seam.

You could put it the other way. It’s a little uncomfortable because you have a seam going beneath your fingers. The guys don’t throw two-seam curve balls very often because they look different. They show like a red railroad tracks. Like when I catch a kid’s two-seam curve ball, I’m like, it just doesn’t look like a fastball at all.

It looks very strange. Um, but with sliders, as I asked around, cause I tried to pick up a slider my last year. I asked eight guys, I got eight different grips just as far as where they put their fingers on the ball and it doesn’t seem like it mattered. The only thing that really mattered was that their fingers are together.

And really it’s just like how you throw it. It almost has like nothing to do with the, with the orientation of the seams. Would you agree or disagree with that? Or do you think that’s a really misguided thing? Would there be one way you would say you should hold it this way because of

Barton Smith: X. Here’s my take.

I’m going to tell you what pitchers think. And I have no idea what pitchers think obviously, but you tell me from Rob, I think when a pitcher grips a ball, they’re usually thinking about, Hey, I want to split as hard as I can and ha having the seam underneath my finger is going to help me do that. That’s the, and so I think that’s when they decide on a grip, that’s usually their primary consideration.

Uh, if you’re trying to throw a seam-shifted wake pitch, I’m going to argue that, um, you’re going to be more successful if you back off of that idea a little bit. Cause the same shift, the white pitch is not about spin. Spin. Doesn’t do anything to it. Um, for or against it. So, uh, then we, we may want the ball to have a certain orientation as it fly.

So I’m going to say, Hey, can you hold it like that please? And, and, uh, uh, they might say, well, why would I do that? I don’t have a grip on a scene. Um, but, uh, uh, that’s I think that the that’s what the revolution she is going to require is that people let go of that idea that I need to seem to hold onto in order to spin the ball.

Dan Blewett: Gotcha. Okay. That makes sense. So, seam-shifted wakes are not going to apply to what pitches like they’re not gonna apply to basketballs or like

Barton Smith: they applied fastballs. You saw two from Jared, just a, I have yet to see a curve ball. I think it could be done. Um, but I think a curve ball is a pitch that you really probably want to focus on the spin I’ve seen.

I’ve seen sinkers four seamers change ups four, four seamers with a lot of gyro change ups. Um, A couple of different kinds of change ups and, and then the new frontier that we have really got into to get a slider. I think there are some possibilities there. Um, one of the issues with sliders, I think you’ve kind of alluded to this and said that are difficult to throw the same way every single time.

Uh, they probably don’t come out of your hand super consistently. So I think that might be one of the reasons that sliders were a little tougher. Um, let me, uh, I’m going to go back to sharing my screen, cause I just want to, I want to run through a few videos, um, that I’ve collected up, uh, have some, some different change ups that I I know about.

Um, let me see here. There we go. Um, this is Kyle Hendricks just recently. Interestingly, he throws his change up two different ways. This one seems to be some shift that needs to could see that seem very prominently. No, the one that we focus on the most is this is a Charizard and that says this good ball, change up the drops here.

I think that’s Michael Augustine’s video. He’s the one that coined that term. Um, this is Waka from a recent game. Uh, so again, you see that seem very prominently. Um, you can see that they’re gripping at different ways, but getting the same at the end of the day, it’s flying through the air the same way. Um, Dan Straley, uh, this was Korean baseball and a ups, hopefully replay.

And there we go. This one’s really, I think, a beautiful one

Dan Blewett: that one looks or that one looks like it’s. Basically rang finger pinky.

Barton Smith: Yeah. And I think it’s about the best I’ve seen. Uh, so he had the interesting, um, position of being the only, or the probably the most prominent American baseball player pitching.

Early in the seat, you know, early back in April. But this one I really wanted to talk about because, because we’ve, we invented a picture, recall the Looper, where you have a seamless, looping around the pole. And it’s something that we came up with just because we could do it in our pitching machine with no gyro.

And this is a Korean pitcher throwing that Looper. Uh, he didn’t learn it from me. He came up with that completely on his own. Um, but, uh, that’s a lot of fun that we, you know, almost anything you could think there’s nothing new under the sun, you know, almost everything has been tried and, uh, sincere later some pitcher somewhere in the world’s getting water into stuff that works real well for reason.

Dan Blewett: Yeah. That loo that, that Looper pitch looked like it was mainly middle finger. Just. Swiping over the top of the base as you. I mean, obviously we’re a pitcher, like the further you get away from the index finger, I feel like the less control and feel you probably have on the ball from now. That’s all nonsense infield.

They’re like when I grabbed the ball, like on the run, Yeah, and I grabbed the ball. If I grab it, ms. Grab it. Like, I want the ball, obviously my index and middle finger, just so I can get full control, at least in what I consider full. You have to think of, even if you’re holding like this, the index finger is just for a stupid, in a sense.

I mean, ultimately it’s going to leave off the middle finger. Like every pitch pretty much leaves off the middle finger. So the middle finger almost long. I mean, it’s significantly longer for most people too. So right when you’re seeing that with a change up, it’s the fact that. This finger on the chain of his, on the descending part of the ball.

So by the time they get there, it looks like there’s only one finger, but they’ve been stabilized the whole way until the, the end with the, so when you’re pitching it, like, are you basing everything off of your middle finger essentially? I mean, that’s where you feel everything come off. Like when I think most pitchers, just get a blister in the middle of like, My middle finger would be blistered and callous, like crazy.

And you feel it. And that’s why if you ever go back to throwing a college, but like this is a college rule, this is a youth ball. But when the college balls had those big seems like I would go home and like inner squad with my Alma mater, they would just chew up. I’d have a blister on my middle finger after like throwing one bullpen with those things, because there’s just so much extra grit on.

Even when, even as a position guy. I mean, I hate throw on your walls. Yeah, and they feel so they feel square barn. We got a question on YouTube, uh, someone who obviously follows the research. You said, what was, what was the estimated success rate when pitchers try throwing a loopers? Do you think they’re easier?

Do you think you’ve changed up to the next wave because they’re easier to achieve high efficiency?

Barton Smith: Uh, well, first of all, I think, uh, if you, if you look at my Twitter feed, I have a, um, I have a pinned tweet to about. With the more, more cowboke I say more gyro, because I think seams shifted. Wake is really going to be about having inefficient pitches.

And one of the unfortunate language problems is trying to explain to somebody that an inefficient pitch can be better. And, and, uh, so when we talk about seam shifted wake, cause I think usually, um, uh, more gyro helps. So the Looper was something that we came up with. Because we needed to be able to test it efficient pitch because we’re throwing them with machine and it can only throw a hundred percent efficiency.

So Looper is a rare orientation that works with no gyro. Um, so yeah, going back to the question, if I, if I understood it, hopefully I understood correctly. Um, We’re not looking for efficient pitches most of the time. I think you might’ve heard me say that if you’re trying to throw a loop or you do want it to be efficient.

And, and the cool thing about that, this is something I was talking about quite a lot a while ago. Um, let me see. Here’s my, I have a Looper ball. This is my Looper ball. So if you see that this is. This is the same looping around that pole. And I would talk about the fact that if you wanted to throw a Looper, forcing, yeah.

Normally I grip my foreseen like this and then hopefully dance that cringing. Cause I’m gripping it wrong. But then if you wanted to throw a Looper know, I need to get that access. Uh, so that it’s, um, kind of spin that way. So I just take my normal four-seam grip and a normal pharmacy in grip. And then I just adjust it.

So that, that rod comes out straight. And then the cool thing about that, and I still think this is a potential cool thing about it. Yeah, it is. I could put the loop on one side or I can put it on the other side. That’s good. Of course the ball in two opposite directions for the same pitch. So, um, that’s an exciting possibility.

And one of the questions that comes up with all this seam shifted wake stuff. Um, the real brass tax questions, does this help you get hit her out? Uh, I was talking to somebody about this last night and he said, well, I think if you could make it, do opposite things at the same pitch and yeah, it would help you get

Dan Blewett: a hitter out.

Barton Smith: And, and, um, uh, so that’s what Hughes’s doing. He’s got opposite effects on the same pitch. And I think the Looper could do that too. And I have no idea if I answered that question.

Dan Blewett: Well, I think he was asking. How good are pitchers at throwing it. Like if they, if they try to do this, do they throw it correctly?

15% of the time, or,

Barton Smith: yeah, I have a, I have a video of Dan arts buffer. Who’s now with the coach of the Bluejays. Um, I visited them in March and he stepped out on in the bullpen and about 10 minutes later he was throwing it. Uh, and the way that we did it, this was an idea that Trevor Bauer gave us. Um, you draw a line on the ball like that, where you want it to spin.

And if, if it works correctly, as it flies, you just see that line sitting straight and it’s a good tool. Um, so basically what I did was put a dot where the rod comes out of my ball. And then I drew a circle around that. And if you do that, um, it doesn’t take long for a picture to figure out, okay. I normally would put my fingers here.

I’m going to need to put them more like that. And then I’m going to get that, that spinning accurately. So I think in the case of the Looper, um, which I’m not necessarily advocating it’s, it’s not very hard to get to learn how to do that as a fastball and to put it on either side of the ball and

Dan Blewett: what distinction.

So what is the Looper do that the disco ball change up doesn’t.

Barton Smith: Uh, it doesn’t do anything. It’s a, it’s a less effective version of a disc of ball. So, uh, let me see if I can explain this. Um, let me get my, uh, correct.

Dan Blewett: So if it’s less effective, it’s just maybe easier to throw, like in what if you could choose either.

Why would you choose a Looper or would you not, you would

Barton Smith: choose a Looper because you throw the ball efficiently. So in that, that tends to be a characteristic of a certain picture. Some people can manipulate it, but, uh, what I’ve seen, most people have a natural tendency to throw the ball efficiently or less efficiently.

If you throw the ball less efficiently, um, then uh, then I would go with more of a disco ball. If you throw out efficiently, I would go with more of a

Dan Blewett: Looper and it wouldn’t be exactly by efficiently.

Barton Smith: Um, more efficiently means less general. With the access moving straight as opposed to tilt it. Okay. Um, and so if you look at a lot of the videos I just showed, you’ll see that a lot of those have a very tilted axis.

And I think that, that, and the reason, the reason that that is helpful is if you look, uh, let me see here, this baseball, if I’m throwing a Looper, the rod is straight up and down. If I’m throwing a disco ball, change up, the rod is tilted and. The idea is in both cases, I’m sorry to be tilted like this. The idea in both cases is to get that scene at some of the top of the ball at the top of the ball.

This one’s there automatically because I’ve, um, I think. Uh, I got that certain orientation. This one requires some gyro to get it there. But what that does is in, in this case, it’s a very narrow range of the scene. That’s having an effect. And in this case, it’s a much wider range of the same, so it’s covering more on the baseball.

And so it has more force. So I think that, that, I don’t know if they clarified anything or not, but I think the disco ball change up. As more of the scene causing an effect than the Looper does. And so I think it gets more force as a result.

Dan Blewett: So going back to the throwing a fast ball as a Looper, um, so you could essentially like set that orientation, throw it, and it would just, w what do you feel like the action would look like?

I mean, have you seen this happen? Like, have you been able to actually have someone like that? Like, what does it do.

Barton Smith: Uh, well, the issue with having a human being through it is it’s very difficult to tell if anything happened. Our tests in the lab say you get five inches of break out of it.

Dan Blewett: It’s not just straight, straight lateral, or is it a combination?

Or what

Barton Smith: if I throw it like this? Yes, it would be that way and down. So it’s at a 45 degree angle. We’re not sure why. Um, I, I planned on that way. I don’t know where the down comes from yet.

Dan Blewett: I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to cut you off, but that five inches is that happening over like how, how far of a distance immediately

Barton Smith: over some of the hall.

Okay. Yeah. So, um, and my point was that if you have, uh, if you’re, if you’re generating five inches of extra break and you’re trying to see that with your eye, I don’t think you can really see it. We, you can see it in the lab because my, my mission, he throws the ball the same way every single time. So I can put the ball in and two different orientations that I could see the five inches difference.

Uh, so. Well, then one of the big challenges, uh, especially from a, like a pitching coach point of view is detecting this. And I think we’ve developed some ways to do that. But, uh, back when I was visiting teams back in March, we didn’t have them. So it was hard to tell when it was working. Yeah. Go back to the, the two pitches I showed you that Jarrett’s or how do you know that he didn’t just throw that four-seam higher?

Um, I can, I actually have ways of tracking his baseball. And I can see through those two pitches at the same trajectory initially. Uh, and, and so I know that that break is coming from seams, but that’s a hard thing. It’s a hard thing to detect perhaps over. Can’t tell you that track, man. Can’t tell you that.

So that’s, that’s one of the big challenges.

Dan Blewett: And I want to cut to that video cause you showed the one disco ball chain and the other one that was like, or maybe that was the laminate, that was the laminar express video that you have. But I want to talk about the difference between that, but before I do, have you ever set up behind home plate for where your can in the shooting and watched it with your eyes as, from a catcher’s point of view?

Barton Smith: I don’t know that I have it’s

Dan Blewett: I feel like you need to do, I think you need to do that. I mean, because honestly, so, and I’m not alone in that lots of pitching coaches play catch with their, you know, their pitching lessons, their clients.

Barton Smith: Yeah. It wasn’t that, I know that view is different and

Dan Blewett: yeah, and I think like, for example, so as I’m trying to picture like this loop or fastball, like it goes five, five, and five, you know, whatever, five inches to the right and five inches down.

Then the question is, is it a good, like terrifying Mariano Rivera kind of cut, like that’s late and scary? Or is it just like, it’s it meandered across the zone over the coal of course, the way. Right. Whereas your data might be able to say that it broke, but maybe it’s like, eh, that’s kind of a sloppy, slow moving pitch.

That’s not really going to get you on out. And you might,

Barton Smith: you reminded me about something. I forgot to say. That’s really important about the disc about change it. Um, so it’s flying that way. Right? And the, the key is that this scene is near a, uh, near the line location of a slice in the middle of the ball.

Dan Blewett: All

Barton Smith: that’s perpendicular to the direction it’s moving to the ball is moving straight. This way, that line is straight up and down. And so say that I threw it like this. What I’m trying to show you is that that seam is not in that location. But now as the ball starts to fall, that this line is going to tilt this way because the direction of the ball is changing.

And so suddenly that seam could be doing something where it wasn’t initially. And I think that that’s what makes the disco ball change of such an awesome pitch. Is it because it has late break or it has that potential? So all this data that we have on, it seems to say it’s being forced downward. I think it’s being forced down, but suddenly at the end, And that’s why change ups.

I think for steamship, the white pitchers are so exciting because the gravity can cause the effect to kick in.

Dan Blewett: Well, now you’ve so most of these disco ball chain ups are a lot faster than traditional change ups. I mean, would you agree? I mean, they’re like, and this is the same with mine. It was the same with the ones that I, that I taught to kids where they’re like, Hey, I’m throwing 60.

This change up is. 55 or like, Dan, that’s not slow enough. I’m like, it’s slow enough when you consider the whole pitch. It’s not just that it’s slow. It’s the fact that also bears down and into a writing. It’s also that it, it sinks a lot too. Right? There’s all it’s. And that’s why, so my friend who’s a scout was talking about this and he pitched in the major leagues and he was saying, Yeah.

Like my whole life, I was taught that a change up just needs to go slower. But now with track, man, it’s grading out all the different qualities of the pitch. And then they’re basically just telling us that no speed is just one thing that even if it’s a little bit harder, like it’s closer to your fastball speed.

The fact that it has all this extra movement. Makes that pitch as a whole, a better quality pitch to get hitters out with is basically what’s happened. So Frankie

Barton Smith: has one facet and his fastball, right. So that kind of blew up the whole idea. And it’s slower. Right?

Dan Blewett: I guess my point was that. So when I talked to Alan, before he was talking about how cutters.

The, the idea of late break is essentially less break. So a cutter is following the fastball path longer before deviates from it, whereas a big, slow loopy curve ball has to deviate interjectory a lot earlier. Right. And so I wonder, I’m wondering out loud and you can interesting your, or your opinion of it, but is it the fact, is it partly the fact that these disco ball change ups are significantly faster compared.

They’re almost like the same speed differentials as a slider. So is the fact that it seems like sharper later breaking is a really, just a product of maybe the velocity and the speed differential or is there more to it than that? Just that,

Barton Smith: yeah. I don’t know if I can answer that, but the only one that I’m really tuned into is Strasberg.

He throws at about 88 miles an hour. He throws his fastball pretty hard. I’m not sure. It’s probably like 95, right?

Dan Blewett: Yeah, I think it’s consistently 93 or 96 these days,

Barton Smith: but I definitely agree that most of the disc balls we look at are pretty hard. I’m an exception would be Hendrix who was probably throwing that 75 miles an hour.

So I don’t think they need to be

Dan Blewett: hard for it

Barton Smith: to work. Um, but to getting back to the light break idea, the late break that you get from a cutter, um, which Allen calls less brake. Is coming from the gyro component and the gyro component becoming none. So one of the funny things about gyro is it, you start with some gyro spin.

If I start with a baseball, that’s spinning like a bullet as it falls. That becomes non gyrus spin. So that’s, that’s a, maybe a little bit mind boggling, but

Dan Blewett: that’s that

Barton Smith: notion of, of light break comes from is that as the ball falls, now, some of that component kicks in where it wasn’t doing anything before that’s example, two Agnes causing late break.

This change of stuff I’m talking about is seam shift, the wake causing late break. I think both are possible. And I think, um, I think it’s a fact that if you can get the ball to move a half an inch, In the last five feet, that’s quite a bit more important than getting it smooth, 15 inches over 60 feet.

Dan Blewett: Can we, since we’ve referenced Magnus a bunch and I, I would explain, you know, when I was teaching a curve ball too good, I’d explained that the Magnus effect and I’d try it.

I’d use the example of an airplane. Could you, again, 12 years old, eight years old, can you give us your engineer’s explanation of a Magnus and how it affects fast balls and curve

Barton Smith: balls? Yeah, I have a really great video for this. Um, and I’m trying to think of where I can grab onto it quickly. Um, I have it in, I don’t want to go plowing through all my, uh, I mean, let me know.

Dan Blewett: We’ll also ramble, ramble while you’re, uh, while you’re looking for it. But

Barton Smith: have you ever seen the video of somebody dropping a basketball off of some huge dam? I

Dan Blewett: haven’t, but that sounds

Barton Smith: cool. Yeah, no, it is really cool. Um, and I’ll find it for you. Uh,

Dan Blewett: but yeah, I mean, I used the, the advisor basically explained to kids that it’s kind of the opposite of the way airplanes take off, like their teardrop shape wing as they accelerate.

Creates high pressure underneath that pushes the plane up. And it’s kind of, that’s how a four seamer is a little bit. And then with curve balls, it’s the opposite of that, that you create this high pressure zone that shoves the ball down as it, as it flies. And that’s why they want to get there, um, forward direction.

I’m spinning. They want to get their tops

a little smooth jazz.

Barton Smith: Yeah. Sorry this, uh, this had some, uh, background music to it. I got that turned off now. Um, let me, yeah, let me show you this demo. Cause I, I think that this is a really good way to show it. Um, And these guys, uh, yeah, I’m sharing now. Right? Okay. So they take this basketball and they just spin it and drop it off at dams.

So why is it? Yeah. Yeah. So it’s gaining speed and that’s why it starts to get more and more Magnus effect as it goes. But the other thing that’s interesting is that the, um, and that this note here is really helpful for understanding it, think about the direction that the front of the ball is moving and the front of the ball, what the front of the ball is, depends on which direction the ball is heading.

Right. So if you think about a fast ball, you gonna go back to the fast ball. Front of the ball is moving that way. Curve ball in front of the ball is moving that way.

Dan Blewett: Oh, that’s a great way to, to break it down. That’s super simple.

Barton Smith: That’s not how it works, but that’s what it does. And I think, I think if I’m trying to teach a pitcher, I would tell them what it does rather than how it works.

Dan Blewett: Yeah. So we’ve got a question. Periscope from Alan Alan asks. How does the rubbing mode effects baseball, aerodynamics? Have you done anything where the bow, where there’s anything on the ball?

Barton Smith: Yeah, so we did one test of that and so I have one data point and it said nothing or mostly nothing. So when, when we rubbed, we bought some mud, we rubbed it on a baseball.

Um, and we did notice at least today later, this seems the baseball world a little higher than before we wrote the mud on it. But w when we tested that baseball, we did not find anything different about the way it behaved. Obviously I think a big impact on a pitcher’s release, you know, it makes the leather feel different.

So I think it has a biomechanics effect. I think in terms of aerodynamics, it’s not much. Well, all that said, um, Rob Arthur had some really interesting comments on baseball perspectives recently, where he thinks that pine tar that’s left on baseball does have an effect in their dynamics. And that’s something I’m really curious

Dan Blewett: about.

Hmm. Hmm. Hmm. So I want to shift to cutters a little bit. So we’ve, we’ve talked a bunch about cutters and this is hard to figure out for a number of reasons. Number one. Very few pictures outside of like, there’s not a lot of data. Like you can’t find a lot of, I mean, obviously there’s MLB data, but you can’t find on a typical high school field.

Anyone that throws it, her that’s good. You can’t throw a youth kid that throws a cutter. That’s like, Proper, I would say, and not many coaches through it. It’s a very rare pitch, especially five, 10 years ago for everyone. Who’s like a coach today. Who’s retired, very tiny percentage of the population ever threw a cutter.

Like it’s big. I think it’s gaining popularity now. We’re in 10 more years, there’ll be a lot more coaches that through it and could teach it. But right now it’s kind of an enigma. I only had one guy who was a teammate who threw a good one in the Mets organization. He taught me mine and I’ll share it.

Cause we we’ve talked about this privately. We’ve kind of talked about this. And Alan’s thing, but my understanding of it, which could be certainly could be wrong was that basically you’re just essentially throwing a four seamer that you’ve tilted slightly upon release. So you’ve tilted it. So it’s flying straight, but it’s tilted with four-seam spin slightly off straight, but you think there’s more of a, so yeah, exactly.

Barton Smith: Trying to throw it like that. But what you did was. A little bit of that.

Dan Blewett: Yeah. So that makes it gyro. Is that correct? You can’t.

Barton Smith: Yeah. Anytime that rod isn’t straight, anytime I tilt that rod this way or that way that’s Chara.

Dan Blewett: So let me share the video that I shared with, um, with Barton. And this was, uh, this was, well, what was interesting is you said.

This was your like nice forcing rounds. Like, I’m pretty sure this was a cutter. So this was a guy I got on video. There’s this release. And it’ll be, that’s hard to tell that it looks like a forest anymore, but it was, he threw all cutters that night.

Barton Smith: Right. And I think you can see that that left side of the ball is closer to home plate than the right side of the ball.

To me. That’s, that’s what makes it a cutter. And I missed it when you showed it to me the first time. But if you look carefully, I think you can see that that ball is a little bit like that.

Dan Blewett: Yeah. And so that makes sense. So what, so I guess, would you say that we, you and I were kind of saying the same thing where, because it’s tilted that’s, that’s where you were saying there’s gyro.

But to me, I like wasn’t even thinking that that’s Gyra. That’s just like the ball stilted, but

Barton Smith: yeah, no, I think cutters have gyro. So I once posed the question. I think you picked up on it as cut and jar the same thing. Um, I think a cutter has a gyro component to it, whereas maybe I think a pitcher that has a cutter and a four seamer, you’re basically changing the amount of gyro they put on that.

Or seamers ideally has very little because you want all that Magnus effect pushing the ball up. Um, but, uh, and then the cutter, I guess at least part of it is that the batter’s expecting that to have the ride and it doesn’t, that’s one thing it has better. The other is that it might have a little bit of sideways movement too, and that movement might happen late.

Dan Blewett: So you shared a, uh, a video of your son who’s you said he was on 13, right. And he was throwing one that had a lot of bullets spin, like a lot of gyrus man, where he clearly got way on the side of it. Yup. And what’s really interesting about all this stuff, because I see cutters being taught more or. You’ll see it around Twitter or on forums or on YouTube, you know, like, yeah.

I was like, yeah, my kids, my kids are 12. He throws a cutter. I’m like the cutter, isn’t it. Isn’t, it’s not a suitable. They think, I think a lot of people think that it’s just suitable corollary to the sinkers, essentially like, Oh, the sinker just goes this way. So why can’t I throw a fastball that goes that way?

Like same, same, exactly the same, um, uh, you know, not effect, but the same use, right? Just a fastball. It’s not straight, but. What you and I were chatting about is that the, um, the cutter is really hard to throw properly where, and what’s, what’s really funny is when, if you want to get a kid to accidentally throw a cutter, the best way to do it is to give them a two seamer to give them a two seam grip.

I see more kids throw and I’ll see it coming at me and it’ll just go rant. Which is kind of scary. Sometimes I’ll have an 11 year old throw an accidental cutter. That’s kind of frightening because it just takes a weird jacket to her and they’ll never be able to do it that way again. Um, why would you think I’ve got a lot of other questions about the color, but why would you think a two seam grip will make kids accidentally cut it?

Any theories? Any theories? I don’t have any,

Barton Smith: but I do it on a different way to get a kid to throw a color. Oh, this is what happened to my son. And Jared Hughes is the one that straightened us out on it. It’s when the pitching distance got bigger and he feels like he has kind of lost the ball a little bit, all of a sudden hands coming off the sides.

So, um, he, he told them, Hey, you know, don’t, don’t worry. Pass the ball, drive over the front leg. And it disappears like that. Uh, I was amazed and we were talking about technology before I had a diamond kinetics ball. We took, I went down a piece of grass. Um, listen to Jarrett’s suggestion and the cut or the Gyra disappeared immediately.

And, um, and we’re about to, we’re now shifting from 55 feet to 60. So I’m really curious if some of his teammates are gonna have that happen again. And I, I have high speed video of some of his teammates, and I can see that some of them are doing this same thing. I don’t know why a two seamer would do that.

Um, for some reason my kid would grip his two seamer with his thumb on it ball and his four seamer. He would, he would tuck it. And, and I think that that’ll generate gyro, especially if you don’t get right underneath there. Right?

Dan Blewett: Yeah.

Barton Smith: Well, good.

Dan Blewett: Just to touch on Dan’s point is that, uh, Zach Britton. When I, my first year was accurate and second year of professional baseball is my roommate.

And hearing him talk about how he’s got it notoriously very, very good sinker, lefty sinker 97 to 99 normally. Um, but we learned how to throw that sinker with someone was teaching them how to throw a cutter. And he started throwing it. How, uh, Calvin Maduro, who was one of the orals, coaches told them, throw it like this as a cutter.

And the ball just kept heavy, sank, heavy sank, and calender, I guess just said, he’s like, I don’t know what you’re doing, but just keep doing that. Cause that’s a good

Barton Smith: pitch. Well, I guess

Dan Blewett: that was, that’s just, I mean, maybe it’s just a, you know, how everyone’s interpreting things differently, but the orientation of what he was doing was causing that heavy sink.

So

Barton Smith: I hesitate to say this because I’m, so I’m starting to know the topic, but I think if you want a sinker, it’s kind of natural put Pat gyro because then the ball doesn’t carry and I’ve got to the point where I can go to a kid’s baseball game and with a radar. And I can tell how much efficiency the fastballs have because of how much they have them.

If I see something that’s coming down quite a bit, but it says it’s 60 miles an hour. I know the kid threw it inefficiently, so it doesn’t have any carry to it. And that’s basically, you could do that on purpose. But, um, I got all excited when I realized that Sam was throwing a cutter by accident and we went and got on a wrap.

So, and I sent the report to another pitching friend and he said, don’t do that. It’s not going to do any good. And I see the point now.

Dan Blewett: Well, and, and if you, if we go back to that video that I was just sharing, I mean, Think of the dexterity and this was my bigger point. Like young kids are struggling just to throw strikes.

Right. And then you’re trying to talk about the dexterity to tilt the ball a handful of degrees. So when I tried to learn this pitch, it was in 2014. I was coming off of Tommy, my second Tommy John surgery. And I couldn’t throw my curve ball for spit. I couldn’t throw my change of free. Well, I personally had a really tough time after both of my elbow surgeries, finding my off-speed stuff.

It’s like I had one season to get myself back throwing hard and like. Finding the zone and then another season to find my off-speed stuff. So in desperation that I couldn’t throw much for a strike to be on my fast ball. And I was kind of getting by, cause I threw hard, I need a second pitch. So I’m like someone helped me.

They’re like throw a cup and I’m like, okay. So I like just jumped into it and just throwing into a game. I was just learning it on the fly, hoping I didn’t get killed and get released. And it was super difficult because these tiny variations in where you release Matt, your chain, your cutter either didn’t cut it all.

Or it became a slider or it backed up and you’re like, good grief. I can throw a curve ball, not perfect. And it’s still a curve ball. Like it still curves a lot. Right. It’s just not my best version. Same thing with a slider thing. Same thing with a change up with a cutter. It’s like, it’s almost a zero sum pitch.

Like yes or no, like did a cut or did not cut at all. And when it doesn’t cut, you just threw an 87 mile per hour fastball down the middle. Right. And that’s really dangerous. And you’re, you’re lucky when they back up, because then they kind of go into the guy and they’re like, Oh, what was that? And they don’t swing.

Um, so that’s the problem is like good body control. There were a lot of things that kept me from being better than I was, but I had really good connection with my fingers and my release and like, understanding of what was going on when I, I kind of like a, like a photograph of each pitch. I could feel like where it was and how I released it.

It’s not a second always fix it, but, um, Ben to ask a kid to do that, you know, a 12 year old that’s walking five, six guys in for nine innings. It’s like that that’s just way beyond their skillset. Um, where two seamers can sometimes work because if they throw a two seam grip and it just does something.

Great, but that also isn’t the case for most kids, either a lot of kids throw dead straight to steamers. And I think that makes sense considering what you said, whereas if you don’t have some something happening to it, it’s just going to go dead straight, right?

Barton Smith: Yeah. A lot of kids do naturally throw a lot of gyro, like we’ve been saying, so mine’s one of them.

So I tell him yet, you know, I would mix that two seamer in there once in a while, it’s going to move a little

Dan Blewett: differently. Can you jump to that video? You have of the, uh, of the laminar express. Cause I want to talk about that. That’s a really interesting. Topic should have been, can have some context.

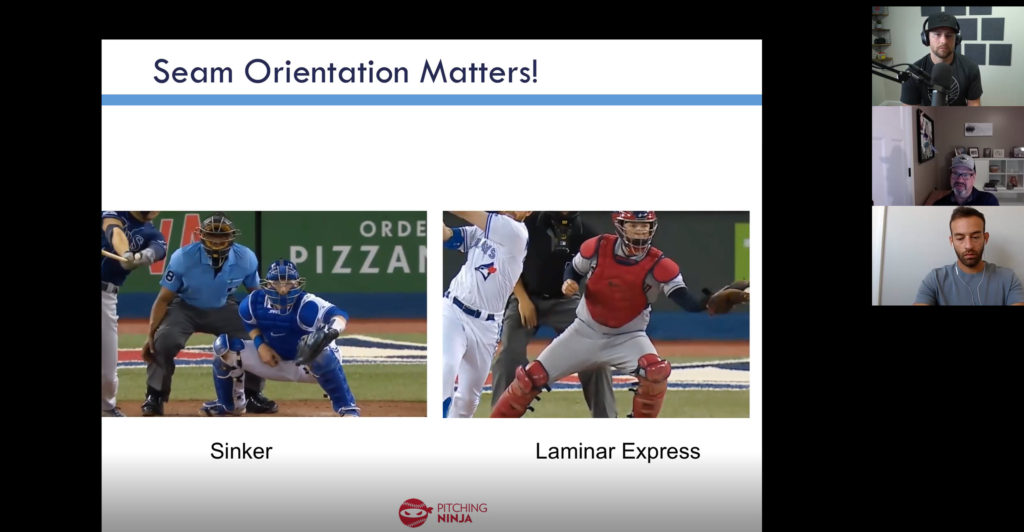

Barton Smith: You’re talking about the Stroman,

Dan Blewett: the Stroman, and I couldn’t tell who the other guy was in there. Yeah.

Barton Smith: Yeah. Um, and yeah, it’s an interesting topic too, because, um, I spoke to Bauer about this, and this is something, this is a theory I have. And it’s a common refrain I hear from people is that this happens when they’re not well, when thinking when something’s off.

So that Stroman on the left, um, power on the right. They’re both throwing a two seamer. Um, you can see the difference in the action, these two seamers, and you can see that Bowers pitch has that prominent seam. It’s up there on the top left to me, this laminar express, it’s almost the same thing as a disco ball with a different axis.

It’s just, it’s, it’s more, you know, access more like this instead of straight up and down. And I use the same baseball. To demonstrate it. And, uh, so, but what Trevor told me about this particular day in Toronto is that he was sick. He had the flu, um, best as back when and people. So, but the work when they have the flu, which I’m sure is over now, but, um, this was happening all day, but he is, uh, he struggles to repeat it.

And I think that is happening is he’s throwing more jar than normal. And all of a sudden he gets this and it’s not natural to think I want more gyro. And so people tend to wander back away from it.

Dan Blewett: So I wanted to share my, so when I initially looked at this, comparing these two, my first reaction is like, you can’t really compare these two because when you look at Straumann’s release, you can see how much on more on top of the ball.